Also Read

Savitri in the role of a wife is depicted as a victim of tyrannical and egoistic husband, Ramani. In the very opening of the novel, Ramani appears as an autocratic husband and father. He forces Babu to go to school despite his having fever. When Savitri tries to intercede on behalf of the child, he rebukes her and insultingly dismisses her by saying that she has no business to meddle with his handling of the children. He finds fault with preparation of food without any reason or rhyme. Savitri bears his unwarranted insults and taunts silently. She does not fume or fire. Rather she retires and sulks in the dingy dark room of the house. She lies there on the floor without taking food and talking to anyone. Her children Babu, Sumati and Kamala feel disgusted and scared of her sulking with her face to the wall. Ramani does not bother about her sulking mood. He goes about his daily routine in the house with an open show of hilarity and humming some tune loudly to demonstrate to his wife that he cares a fig for her. He knows that she will come out of the dark room herself when her surly mood passes off.

The same sort of autocratic behaviour on the part of Kamani gets reiterated in the incident of the Navaratri festival in the house. The light of the house goes off because of some defect in the electric arrangement improvised by Babu in the dolls pavilion. When Ramani returns home, he finds the whole house in darkness. That is enough to flare him up into an uncontrollable rage. He shouts at everybody in the house and recklessly curses them. He beats Babu badly when he comes to know that things have gone wrong because of the latter's interfering with electric system. Savitri cannot stand his inauspicious cursing on the auspicious day of Navaratri. She finds herself helpless before him and has no alternative but to retire mutely into the dark room. She has little education and is rendered totally helpless at the hands of a dictatorial husband.

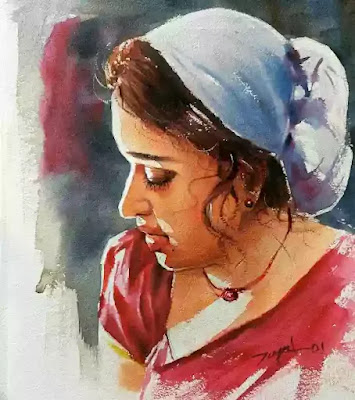

Savitri bears the disregardful attitude of her husband which is evident in his whimsical behaviour with her. She is scolded or fondled by him through a boisterous show of love-making in the presence of his children or the cook at his will. Her personal feelings and individuality receive no consideration. She has to dance to his moods however irrational they may be. She is considered nothing more than a slavish automaton that should automatically respond to him in the way he likes. The incident of going to the theatre reveals his monopolistic medieval attitude towards his wife. He takes Savitri alone to the Palace Talkies one evening. She looks impressive, dressed in her blue saree. He feels proud of her as she is in his possession and other people are envious of him. He surveys her slyly "with a sense of satisfaction at possessing her." The phrase "possessing her" is significantly used here as the author intends to suggest that his wife to him is like one of his so many household material possessions and commodities such as good pieces of furniture, cupboards and utensils etc. He is proud of her in the way he is proud of his good-looking domestic articles. To him she is no more than the possession of depersonalised insensate wooden or metallic gadgets. Time and again, he bears out incorrigibly this reactionary bourgeois attitude towards a woman's (specially wife's) position in the society.

Savitri shows remarkable patience and puts up with her husband's tantrums and slights till the time his nuptial bonafides are not suspect. Innuendoes and suspicions about his matrimonial fidelity prove to be the proverbial last straw on the camel's back. The rebel in her bursts out. Ramani's amorous relations with Shanta Bai who has been employed as Insurance agent in the Engladia Insurance Company brings out a storm in Savitri's family life. Ramani keeps away from home enjoying night escapades with Shanta Bai. This results in complete alienation between Ramani and his wife. Her doubts become a certainty when Gangu, her neighbour, discloses to her that many stories are getting afloat about her husband. She tells her that she has seen her husband in the company of a woman at the theatre at night. This upsets and disturbs Savitri thoroughly. She thinks that the other woman may be more beautiful than she is, the mother of three children besides two miscarriages. In an effort to win her husband back, she decorates herself with ornaments, dresses herself well and wears Jasmine flowers in her hair. She waits for him to return home at night. But to add to her woe, he stays away from home that night in the company of Shanta Bai. Unwittingly, she falls into sleep and finds her decorations disorderly when she wakes up.

Savitri's cup of patience is completely filled up. When Ramani comes home the next night, shedding away her old habitual weakness and tolerance, she asks him bluntly to leave that woman i.e. Shanta Bai. He does not want to face her straightaway. He makes a demonstration of love to her in order to divert her attention. She resists all his beguiling moves and reasserts that he should give her a categorical assurance that he will leave that 'harlot'. He tries to catch hold of her in an effort to fondle her. She gets free of his hold and speaks with an anguished heart, "I am a human being. You men will never grant that. For you we are play-thing when you feel ike hugging, and slaves at other times. Don't think that you can fondle us when you like and kick us when you choose." This outburst shows her defiant, rebellious mood against the tomfoolery and ostentatious, insincere feeling of her husband. His prevarication on this point infuriates her into giving a threat that she will leave the house once for all in case he does not give her an unconditional, clear commitment. He curtly remarks that she can leave the house at once if she so desires. She feels piqued at it and raves against the helpless condition of a woman in the male-dominated milieu of the Indian society. A woman's possession is her body only. All else belongs to the male person like a husband, a father and a son. She bursts out:

"What possession can woman call her own except her body? Everything else she has is her father's, her husband's or her son's."

Hence, Savitri removes all her ornaments and throws then at the feet of Ramani because she does not want to take away anything that belongs to him. However, Ramani tells her that the ring, the necklace and the stud are her father's gifts. She refuses to take them saying. "They are also a man's gift." The rebel in her asserts and she leaves her husband's home at mid-night. Ramani callously shuts the door of the house upon her exit.

Desertion of the husband's house is an overthrowing of the age-old, inherited burden of tradition which binds a woman to home and denies her freedom to get released from her husband's hold however unjust he may be. It is considered a sacrilegious act. For the first time, she is out at such an unusual hour. She gets caught into the cross-currents of thoughts passing through her mind. Driven into a mood of desperation, she sees hardly a difference between a married woman and a prostitute. She says, "The prostitute changes her men but a married woman does not. That's all, but both earn their food and shelter in the same manner." Her bitter utterance reveals the sad, helpless plight of a woman in the Indian middle-class society.

Savitri's pathetic, rudderless condition gets further intensified by her obsessive thoughts about her children. Unable to go anywhere, she enters into the neck-deep water of river Sarayu for the purpose of committing suicide by drowning herself. She gets uprooted by the force of the current. Spurred by an instinct of self-preservation, she cries out for help. Coincidentally Mari, the village blacksmith on his way back home from the town, hears her cries and saves her. He leaves her lying on the river bank. He brings his wife, Ponni, from the village Sukkur to Savitri's side. They persuade her to come to their village. She refuses saying that she will live in the open and will not share food or shelter at anybody's mercy. She takes a vow that she will eat only that food which she earns by her own labour. She resolves to become self-reliant. She is in revolt against the traditional concept that a woman depends on father in girlhood, on husband in womanhood and on her son in old age. She emerges a new woman. This transformation is brought about by a newly awakened consciousness in her for an economically self-reliant status in society. The position of subservience to man remains no more tolerable to her owing to the exploitation of her dependent position by. Ramani for the sake of perpetration of tyranny and injustice to her. Savitri's recent awareness is a precursor of the on-set of Women's Lib. movement which cones to full fruition in Narayan's later women like Daisy in The Painter of Signs etc.

Savitri's sojourn in search of an independent entity begins with her arrival at Sukkur village. She undergoes new experiences which chasten and transform her personality. She reaches hitherto unknown vista of self-knowledge. Her insistent refusal even to accept fruits from Ponni to eat forces Ponni and Mari to find some job for her in the village. They fail to get a job for her in a house. Ultimately, she is employed by the priest in the village temple for cleaning and sweeping the shrine and its whereabouts on half a measure of rice and a quarter of an anna each day. A dingy, semi-dark room in the temple is spared for her to stay. At night left alone in that room, she is upset by nightmarish fears. She feels home-sick and remembers her children nostaligically. She compares the comfort, security and unloneliness of her home with the present predicament. She prefers the former to the latter one. The next day, she returns to the family circle of her children.

Her coming back home shows Savitri's acceptance of things as they are. Her reconciliation or adjustment with the status-quo is the result of a realisation on her part that since the situation cannot be changed, one should accept it. She finds through. her own experience and effort that a woman's place is only by her husband's and children's side. Out of her husband's home, she realises her position of utter helplessness and isolation. She remarks "I am like a bamboo pole which cannot stand without a wall to support it. 'A part of her' which makes her fussy and over-anxious about her husband's homecoming is no more there and a faint stirring of personal life begins in her another part and yet her still another part i.e. the Indian habit or gift for acceptance as strong in the middle-class as in the peasants ultimately prevails. Still, she is a new, changed woman who comes to discover in herself atleast "a - fleck of peasant sturdiness." She does not have the same sentiment of belongingness to her husband's home. The incident at the end of the novel proves it. She wants to call Mari to give him food and some present when he is passing through the street shouting "Umbrella repaired. Sirs, lock repaired." She sends Ranga; the servant but immediately checks him thinking, "Why should I call him? What have 1?"

Savitri may be rated as a forerunner of the Women's Lib. movement which comes to acquire more strident note later on. Her defiance of the age-old accepted traditional fetters is short-lived. Still, she creates a stir in the unquestionable male-dominated orthodox milieu of Malgudi. From this point of view, she stands somewhere between Janamma and Gangu who are her friends and neighbour. Janamma's counsel to Savitri, when she is sulking in the dark room, is representative of the classical Indian concept of the wifely function and duty. She says:

"As for me I have never opposed my husband or argued with him at any time in my life. I might have occasionally suggested an alternative, but nothing more. What he does is right. It is a wife's duty to feel so."

But Savitri does not follow this dictum in toto. Gangu, on the other hand, represents a different way of life and thought. She is educated and nurtures the ambition of making a career as a film actress or a woman delegate from Malgudi. She has a complete sway over her husband who is a teacher and assists her in the fulfilment of her ambition. Savitri differs from her also as she harbours no ambitions and falls a victim to a dictatorial, whimsical and arrogant husband. Moreover, she feels complacent with her limited role of a home-bound housewife.

Besides her wifely role, Savitri is presented as a kindly, affectionate and considerate mother. She nurses her children with full dutifulness. She feels concerned about her son, Babu, who has been perforce sent to school by Ramani despite the fact that he suffers from fever. She does not want him to go to school in that condition. She advises her daughter, Kamala, not to come running in the street during school recess lest she should stumble over and get hurt. She insists upon Sumati to take more of rice and curd in the recess as she is too weak and frail in body. On the day of Navaratri festival, she makes the children arrange dolls and images of various gods, goddesses and animals in the pavillion. The spirit of the Occasion is marred by Ramani's anger, rebuke and imprecations as he is infuriated by the prevailing darkness in the house because of failure of the electric system. Such an ominous behaviour of her husband is intolerable to her. She cannot cope with him and hence retires into the privacy of the dark room. She comes out of the dark room for the sake of children when Janamma tells her that her sulking mood will spoil the spirit of the festival for the children. While leaving her husband's house, she wants to take the children with her. But she changes her mind afterwards on the basis of the argument that they too belong to her husband. She says that she has no claim upon them because her husband "paid the midwife and nurse" at the time of their birth and now pays "for their clothes and teachers." Still, she expresses her concern for them by saying "What will they do without me?"

While away from home, she is continually obsessed with thoughts about the children. Sitting on the steps of river Sarayu in the night, she thinks whether the children are asleep or awake. Left alone in the dark, dingy room of the village temple at Sukkur at night, she feels home-sick and remembers her children nostagically. She can stand no more separation from them. The maternal instinct in her asserts itself. She decides to go back to the homely warmth of her children. Her motherly affections overpower her previous rebellious, bitter self. She comes back home for the sake of her children. The children too are overjoyed at the return of their mother. She is a pious, religious-minded woman and worships gods daily.