Also Read

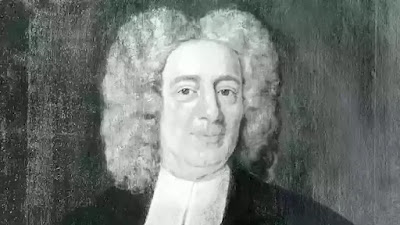

LIFE AND PERSONALITY.— Cotton Mather, grandson of the Rev. John Cotton, and the most distinguished of the old type of Puritan clergymen, was born in Boston and died in his native city, without ever having traveled a hundred miles from it. He entered Harvard at the age of eleven, and took the bachelor's degree at fifteen. His life shows such an overemphasis of certain Puritan traits as almost to presage the coming decline of clerical influence. He says that at the age of only seven or eight he not only composed forms of prayer for his schoolmates, but also obliged them to pray, although some of them cuffed him for his pains. At fourteen he began a series of fasts to crucify the flesh, increase his holiness, and bring him nearer to God.

Cotton Mather was a son of Increase Mother and the illusion of John Cotton and Richard Mather, the two important lenders of the first generation of British immigrants to America As, a prodigy, he entered Harvard University at the age of 12 and prepared devotedly for the ministry. In 1685, he was ordained and soon after became co-minister with his lather of the Second Church of Boston. In 1089, he took some “possessed” girls into his home to observe and treat them with the healing touch. He wrote about these cases in Memorable Providences Relating to Witchcraft and Possession (1689). In course of time he published another account of the Salem witch trials and other instances of the what he believed to be the operation of the evil spirits on the innocent in his next book Wonders of the Invisible World (1693). The colonial literature of New England is incomplete without the mention of Cotton Mather, the master pedant. Being the third in the fourth generation of Mather dynasty of Massachusetts Bay he wrote about New England at length in over 500 books and pamphlets.

Mather’s Magnolia Christi Americana (Ecclesiastical History of New England 1702) is the most ambitious work, which exhaustively chronicles the settlement of the New England through a series of biographies. The huge book presents the holy Puritan errand into the wilderness to establish God’s kingdom. The nature of book is of narrative progression of Representative American “Saints’ Lives.” Also, he published numerous sermons expounding the Puritan doctrine. His religious zeal somewhat redeems his pompousness of style: “I write the wonders of the Christian religion, flying from the deprivations of Europe to the American strand.” By many, he was known as the pre-eminent spokesman for the Puritan culture. In addition to the religious books, he wrote some scientific works also - The Christian Philosopher (1720) and Bonifacious or Essays to Do Good (1710). The Philosopher includes Mather’s keen observations of the natural world on scientific lines with suggestions of their spiritual significance. The Angel of Bethesda (1722) was sort of a medical book. Among his other works were Predator (1724), a biography of his father, “Patema”, and an unpublished autobiography written in two volumes for his children, Psalterium Americanum (1718) and Manuductio ad ministerium (1726). His lifelong project Biblia Americana, is said to be a systematic commentary on the Bible which remained unpublished even at his death.

He endeavored never to waste a minute. In his study, where he often worked sixteen hours a day, he had in large letters the sign, "BE SHORT," to greet the eyes of visitors. The amount of writing which he did almost baffles belief. His published works, numbering about four hundred, include sermons, essays, and books. During all of his adult life, he also preached in the North Church of Boston.

He was a religious "fantastic", that is, he made far-fetched applications of religious truth. A tall man suggested to him high attainments in Christianity; washing his hands, the desirability of a clean heart.

Although Cotton Mather became the most famous clergyman of colonial New England, he was disappointed in two of his life's ambitions. He failed to become president of Harvard and to bring New England back in religious matters to the first halcyon days of the colony. On the contrary, he lived to see Puritan theocracy suffer a great decline. His fantastic and strained application of religious truth, his overemphasis of many things, and especially his conduct in zealously aiding and abetting the Salem witchcraft murders, were no mean factors in causing that decline.

His intentions were certainly good. He was an apostle of altruism, and he tried to improve each opportunity for doing good in everyday life. He trained his children to do acts of kindness for other children. His Essays to Do Good were a powerful influence on the life of Benjamin Franklin. Cotton Mather would not have lived in vain if he had done nothing else except to help mold Franklin for the service of his country; but this is only one of Mather's achievements. We must next pass to his great work in literature.

THE MAGNALIA.—This "prose epic of New England Puritanism," the most famous of Mather's many works, is a large folio volume entitled Magnalia Christi Americana: or the Ecclesiastical History of New England. It was published in London in 1702, two years after Dryden's death.

The book is a remarkable compound of whatever seemed to the author most striking in early New England history. His point of view was of course religious. The work contains a rich store of biography of the early clergy, magistrates, and governors, of the lives of eleven of the clerical graduates of Harvard, of the faith, discipline, and government of the New England churches, of remarkable manifestations of the divine providence, and of the "Way of the Lord" among the churches and the Indians.

We may to-day turn to the Magnalia for vivid accounts of early New England life. Mather has a way of selecting and expressing facts in such a way as to cause them to lodge in the memory. These two facts about John Cotton give us a vivid impression of the influence of the early clergy:—

"The keeper of the inn where he did use to lodge, when he came to Derby,would profanely say to his companions, that he wished Mr. Cotton weregone out of his house, for he was not able to swear while that man was under his roof…."The Sabbath he began the evening before, for which keeping of theSabbath from evening to evening he wrote arguments before his coming toNew England; and I suppose 'twas from his reason and practice that theChristians of New England have generally done so too."

We read that the daily vocation of Thomas Shepard, the first pastor at Cambridge, Massachusetts, was, to quote Mather's noble phrase, "A Trembling Walk with God" He speaks of the choleric disposition of Thomas Hooker, the great Hartford clergyman, and says it was "useful unto him," because "he had ordinarily as much government of his choler as a man has of a mastiff dog in a chain; he 'could let out his dog, and pull in his dog, as he pleased.'" Some of Mather's prose causes modern readers to wonder if he was not a humorist. He says that a fire in the college buildings in some mysterious way influenced the President of Harvard to shorten one of his long prayers, and gravely adds, "that if the devotions had held three minutes longer, the Colledge had been irrecoverably laid in ashes." One does not feel sure that Mather saw the humor in this demonstration of practical religion. It is also doubtful whether he is intentionally humorous in his most fantastic prose, such, for instance, as his likening the Rev. Mr. Partridge to the bird of that name, who, because he "had no defence neither of beak nor claw," took "a flight over the ocean" to escape his ecclesiastical hunters, and finally "took wing to become a bird of paradise, along with the winged seraphim of heaven."

Such fantastic conceits, which for a period blighted the literature of the leading European nations, had their last great exponent in Cotton Mather. Minor writers still indulge in these conceits, and find willing readers among the uneducated, the tired, and those who are bored when they are required to do more than skim the surface of things. John Seccomb, a Harvard graduate of 1728, the year in which Mather died, then gained fame from such lines as:—

"A furrowed brow,Where corn might grow,"

But the best prose and poetry have for a long time won their readers for other qualities. Even the taste of the next generation showed a change, for Cotton Mather's son, Samuel, noted as a blemish his father's "straining for far-fetched and dear-bought hints." Cotton Mather's most repellent habit to modern readers is his overloading his pages with quotations in foreign languages, especially in Latin. He thus makes a pedantic display of his wide reading. He is not always accurate in his presentation of historical or biographical matter, but in spite of all that can be said against the Magnalia, it is a vigorous presentation of much that we should not willingly let die. In fact, when we read the early history of New England, we are frequently getting from the Magnalia many things in changed form without ever suspecting the source.