Also Read

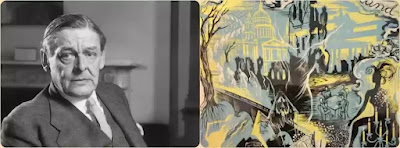

T.S. Eliot, in his treatment of the central theme of The Waste Land, may be regarded as a defender of the moral imagination, with its roots in religious insight and in the continuity of civilization.

Legend of the Grail: At the heart of this poem of exploration lies the legend of the Grail, and more especially the symbol of the Chapel Perilous. How may a man be born again and a blasted land made to bloom a new? Why screw your courage to the sticking-place: dare to ask terrifying questions, and you may be answered. In some versions of the Grail Legend, questing knights who entered the Chapel Perilous-ringed about with tombs-beheld the cup, the lance, the sword, the stone. If they found the hardihood to inquire, they would be answered: they would be told the meaning of these things; told at once, perhaps, or perhaps later. And of that questioning great good would come: the Fisher King's wound would be healed, and the desolate land would be watered again. "So, in a civilization reduced to a heap of broken images' all that is requisite is sufficient curiosity." Hugh Kenner comments keenly: "The man who asks what one or another of these fragments means... may be the agent of regeneration. The past exists in fragments precisely because nobody cares what it means, it will unite itself and come alive in the mind of anyone who succeeds in caring... in a world where we know too much, and are convinced of too little.

Myth and Moral Imagination: Knowing that past and present really are one, Eliot draws upon the myths and the symbols of several cultures to find the questions that we modern ought to ask. Myth is not falsehood; instead, it is the symbolic representation of reality. From ancient theological, poetical and historical sources, burningly relevant to our present private and public condition, we summon up the moral imagination. We must essay the adventure of the Chapel Perilous if we Would not die of thrust, we must confront the Black Hand and the dead wizard Knight, therein the ruinous Chapel; if we face down the horror, and dare to ask the questions, we may be heard and healed.

Past as Present: One of the adverse criticisms of The Waste Land advanced is that "Eliot is snobbishly contrasting the alleged glory and dignity of the Past with what he takes for the degradation of the democratic and industrialized Present. This is historically false, and ought to be repudiated by all Advanced Thinkers." But that is not at all Eliot's intention. The Present, Eliot knew, is only a thin film upon the deep welt of the Past: the Present was ceasing to exist even as he wrote at Moorgate or at Lausanne; the Present evaporates swiftly into the cloud of the Future; and that Future, too, soon will be the Past. The ideological cult of Modernism is philosophically ridiculous, for the modernity of 1975, is very different from the modernity of 1921'. One cannot order his soul, or participate in a public order, merely by applauding the well-o-the-wisp Present. Our present private condition and knowledge depend upon what we were yesterday, a year ago, a decade gone; if we reject the lesson of our personal past, we cannot subsist for another hour. Just in it is with the commonwealth, sustained by a community, of souls: if the community rejects its past - If it ignores both the insights and the errors of earlier generations - then soon it comes to repeat the worst blunders of past times. Whether or not Time is a human convention merely (on which point Eliot had not made up his mind as he wrote The Waste Land), the past is not dead, but lives in us; and the Future is not a fore-ordained Elysium, but the product of our own decisions in this vanishing moment that we enjoy or endure.

No Glorification of the Past: The Waste Land, then, is no glorification of the past. What the reader should find in this poem rather is Eliot's understanding that, by definition, human nature is constant; the same vices and the same virtues are at work in every age; and our present discontents, personal and public, can be apprehended only if we are able to contrast our present circumstances with the challenges and responses of other times. Aside from this, Eliot's glimpses and hints of a grandeur style and a purer vision in other centuries are chiefly the established devices of the satirist, who awakens men to their parlous condition of abnormality by contrasting living dogs with dead lions.

Search for Direction: When one is lost, one must ask for directions; and those directions do not come from living men only. For authoritative guidance, Eliot turned especially, in this poem, to Saint Augustine, the Buddha, and the Upanishads. "The unexamined life is not worth living as Socrates told his disciples. The Waste Land is the endeavor of a philosophical poet to examine the life we live, relating the timeless to the temporal. A Seeker explores the modern waste land, putting questions into our heads; and though the answers we obtain may not please us, he has roused us from our death-in-life. For just that is the Waste Land; the realm of being who think themselves quick, but who exist only in a condition sub-human and sub-natural, prisoners in Plato's cave.

Tremendous Questions: In The Waste Land, tremendous questions echo around the Chapel Perilous. In the progress of a terrifying quest, some wisdom is regained, though no assurance of salvation. We end by knowing our peril, which is better than fatuity (foolishness): before a man may be healed, he must recognize his sicknesses.

Regeneration is a Cruel Process; so commences The Burial of the Dead," the first of the four parts of The Waste Land: the half-life underground seems preferable to many. No sooner is this said than there breaks in the querulous voice of a woman, Marie encountered in an Alpine hotel, hotel, perhaps overheard in chance conversation. She is a displaced or stateless person from the wreck of the Austro-Hungarian structure, With memories of staying at the archduke's her cousin's the mountains conceal her, and she takes that for freedom; her roots withered, she drinks coffee in the Hofgarten, and drifts. Such is the condition of Europe in 1921, for Heartbreak House is roofless on the Continent, too. As she falls silent, a voice is heard, prophetic or ghostly, inviting the son of man to take shelter under a red rock, where he will be shown fear in a handful of dust. The next moment, memory and desire have wafted in the hyacinth girl, the image of lost love; four lines from Tristan and Isolde summon her up from the dead, in this month of lilac and hyacinth and illusory spring. The episode in the hyacinth garden had been like the trance of those who sought the Grail but were unworthy. The hyacinth is withered now, and the girl vanished, amid stony rubbish. Aye, that episode's done for: will the future bring consolation?

Denial of re-birth: So we come to Madame Sosostris, with her. Tarot cards, decadent sibyl misreading her own pack. Fear death by water, she says, to people perishing of thirst. He counsels would deny us re-birth through grace in death, the fertilizing power of water; she does not find the Hanged Man-Christ, or the Dying God in the fortune she tells. But perhaps, unwittingly, this witch has conjured up a ghost: Stetsons, who died a coward at Mylae - which might have been the Dardanelles, these wars having much of a likeness. Thus The Burial of e Dead concludes with the Searcher's reproach to dead Stetson, not far from London Bridge:

That corpse you planted last year in your garden,Has it begun to sprout? Will it bloom this year?Or has the sudden frost disturbed its bed?O keep the Dog far thence, that's friend to men,Or with his nails he'll dig it up again!

The Dog of these lines has beer, explained variously, For William-son, Dog "becomes a sign of the rising of the waters and is friendly to growth." For Maxwell, "the Dog may be spiritual awareness or conscience, which Stetson does not attempt to arouse, in the fear that it might force him to recognize his spiritual failings, to attempt to redeem himself." Cleanth Brooks says: "I am inclined to take the Dog.. as Humanitarianism and the related theories which, in their concern for man, extirpate the supernatural-dig up the corpse of the buried God and thus prevent the rebirth of life." He adds a footnote: "The reference is perhaps more general still; it may include Naturalism, and Science in the popular conception as the new magic which will enable man to conquer his environment completely."

Would it have been well to be disinterred by the Dog, or not well? Eliot never explained, and such controversies may continue so long as English poetry is criticized. This catacomb, layer upon layer, of evocation and suggestion in The Waste Land makes this poem subtle and strange and ambiguous as the Revelations of Saint John. Many lines are puzzling as the characters written by the sibyl on the leaves she scattered. Yet the general meaning of The Waste Land is as clear as its particular lines are dark.

A Heap of Broken Images: So the Seeker clambers over the heap of broken images, leaving "The Burial of the Dead," to enter upon A Game of Chess the second part of the poem and he stumbles into a boudoir. At first, this room is mistaken for Cleopatra's; but really this is no chamber of grand passion and queenly power; it is only the retreat of a modern woman, rich, bored, and neurotic. On a wall, the picture of the metamorphosis of Philomela is a symbol of the reduction of woman to a commodity - often a sterile or stale commodity - in modern times. Modern woman is ravished, but nowadays she is transformed into no sweet nightingale. In this boudoir the woman is haunted, starting at noises on the stair, seeking in empty talk the quieting of a subtle dread; no diversion satisfies her-surely not "O O O O that Shakespearean Rag" "Think", she tells the Seeker; and indeed he does;

I think we are in rats' alleyWhere the dead men lost their bones.

So it is with the woman of fashion-and not otherwise with the woman of the ladies' lounge of the London public house, talking of adultery and abortion. The game of chess that modern woman plays is her undoing; sexual power is atrophied to the parched attempt at gratification of an appetite which cannot be satisfied by flesh only; love becomes an empty word. And the bartender calls out repeatedly, "HURRY UP PLEASE ITS TIME": like the woman of the boudoir, the woman of the pub idles away the hours and days and years until death knocks.

Symbols of Decadence: Leaving the pub, the Seeker drifts down the Thames: we hear the Fire Sermon, the third part of this poem. The polluted river does not cleanse; dull lusts, sexual or acquisitive, hang about it now; the Seeker finds no gaiety and no glory. He becomes hermaphrodite Tiresias, importantly witnessing copulation without ardor and loss of chastity without either pleasure or remorse: When lovely woman stoops to folly and Paces about her room again, alone, She soothes her hair with: automatic hand, And puts a record on the gramophone.

Against this degradation, the Seeker appeals to the true City of love and gaiety, with music upon the waters. One hears, as a distant echo, the voices of children singing of the Grail. But the Fisher King himself, perhaps the wounded Fisher of Men, casts his lines in a dull canal behind the gas-house, even the romantic memory of his crumbling castle departed. Here the dead do not rise to the surface, their bones being cast into a dry garret and "rattled by the rat's foot only, year to year." From Highbury down to Moorgate Sands, this river, once life-bestowing has turned sinister. The varieties of concupiscence have driven out love. Those who amuse themselves beside the river or drift down it (to their undoing) fancy that they are safe enough:

But at my back in a cold blast I hearThe rattle of the bones, and chuckle spread from ear to' ear.

Infatuation with transitory impulses, the Buddha had said in his Fire Sermon, oppresses man; abjure desire. And as Augustine sought redemption from the unholy loves of Carthage, so the Seeker prays that the Lord may pluck him as a brand from the burning.

Death-a gateway to life eternal: Out of sea the Thames carries us and to the ten enigmatic lines of the fourth part of this poem, "Death by Water." Passing beyond profit and loss, Phlebas, the drowned Phoenician entered the whirlpool; yet what we have taken for "life" may be worse. than death; and perhaps through dying, we come to the life eternal. Madame Sosotris had predicted death by water. Yet is this 'dying' realy annihilation? May it not be rebirth, as by baptism? However that may be, a surrender to the element of water is better than endless torment in the fire of lust.

Mist of Uncertainties: It is not in the ocean depths that the Seeker ends his quest. In the concluding part of this poem, What the thunder said, he ascends into the mountains, once the source of life-giving water, Gethsemane and the slaying of God in his mind. The "red sullen faces" that sneer upon him from "doors of mud cracked houses" are God-forsaken; the thunder is dry and sterile. Someone walks beside him: the Fisher King, perhaps, who once guarded the Grail; and a mysterious third being, hooded. Is this the Christ, or the Tempter of the Wilderness, or some Hollow Man? In this delusory desert, the traveler can be certain of nothing.

The Topsy-Turvy World: This upland desolation, ravaged by hooded hordes, is the waterless expanse of Sinai for lost people of this century and many centuries-who wander aimlessly, uprooted by terrible events; it is the Eastern Europe of 1921, and also the "Hell or Connaught" of all the vanquished. "Cracks and reforms and bursts in the violet air" of twilight work the ruin of cities: Athens and Alexandria and Vienna and London become as the Cities of the Plain; the terrible simplifiers contend against one another in the Last Days. Here the landscape is by Bosch or Breughel, and woman's sexuality, sunk into witchcraft, engenders a brood of monsters, "bats with baby faces." The world is turned upside down; voices call from dry cisterns and wells. Threading his way upward through this horror, the Seeker arrives at the Chapel Perilous, dry bones and tumbled graves. Empty and forgotten the Chapel stands, "the wind's home" Yet the Seeker has arrived at the place where, even now, questions are answered in the moonlight for those who dare to ask in earnest. At a cock's crow from the roof top the diabolical powers round about the dispersed for the moment. A damp gust bring rain, and the thunder speaks.

The Voice of Revealed Wisdom: That thunder is the voice revealed wisdom: it is the Indo-European "DA," a root from which has sprung up many trunks; it is, if you will, the "I am that am" from the Burning Bush. And the thunder of "DA" utters three sounds that are the answers sibylline indeed-to the Seeker's questions. They are "datta "dayadhwam" and "damyata," from the Brihadaranyake-Upanishad. And they signify "give," "sympathize," and "control," So saith the Lord; give, sympathize, control. But though the Seeker had found courage to carry him to the Chapel Perilous and to ask the dread question, has he resolution and faith sufficient to induce him to obey the thunder? Some rain has fallen; but the sacred river wants a flood; mind and flesh are feeble. For lack of human daring, the Waste Land may remain ghastly dry.

Surrender of Self: Give? That means surrender, yielding to something outside one's self. If sexual union is to be fertile, there must occur surrender of self in some degree, momentary self-effacement in another. Lust, too true, may produce progeny; but those are the bats with baby faces. Larger even than procreation, giving or surrender means the subordination of the self (as of the arrogant private rationality) to an Authority long derided and neglected. Can modern man humble himself enough to surrender unconditionally to the thunder from on high?

Sympathize? That means love and loyalty, and the diminishing of private claims. We all lie in the prison-house of self-pity; and to recognize the reality of other selves-more, to act upon that reality-must requires unusual strength: the virtue of clarity. The overweening modern ego has grown fat on the doctrine of self-admiration; the community of souls has been falling apart for some centuries now.

Control? That, as Babbitt had said, is to place restraints upon will and appetite, True control is exerted not through force and a master, but by self-discipline and persuasion of others. But can the strutting will restrain itself by its own act? Can modern appetites, so long unchecked so long gorged on blood and foulness as during the War - be confined once more to their proper place? We have indulged the libido; now can we return to the other kind of freedom, voluntas - to Cicero's ordered and willed freedom? Our desire are insatiable, and the thunder is distant.

Recovering the Spiritual Order: So the thunder has answered the questions that were put in the Chapel Perilous. It was painful to seek for those answers, it will be agony to obey. Still, the Seeker hesitates, though now the arid plain is behind him. He casts his lines upon the waters, London Bridge is falling down. The outer order of civilization disintegrates. But may not ruins be shored up? And should not a man commence the work of renewal, spiritual and material, by setting his lands in order: by recovering order within his own soul? The world may divide as folly such aspirations; but this is a mad world, my masters. Play Quixote, Give, sympathize, control; and the peace that passes all understanding be upon you.